Collections by Name | Collections by Region

United States Presidential Campaign Buttons

The political button, or lapel pin, is one of the forms of material culture most associated with political campaigns in the United States. The presidential political campaign buttons in the collections of the MSU Museum number over 140, come from many sources, and represent a wide variety of candidates.

The first political pins were actual buttons sewn to lapels and worn as early as April, 1789, at the inauguration of George Washington as the first president of the United States. Photographs of candidates first appeared on buttons in the 1848 presidential campaign. A sew-on Abraham Lincoln badge from his 1860 election is the oldest button in the collection, and is one of over 300 varieties produced that year. The picture in the center is called a ferrotype, or a tintype, where the photograph was developed directly onto a lacquered sheet of iron that had been coated with collodion (a syrupy solution used to develop photographs). It was then exposed, washed, and varnished. Ferrotypes were typically encased in a circular or oval brass frame with a slogan around the rim. The other Lincoln badge in the collection is an 1864 ferrotype shell badge, which meant it was pinned to clothing instead of being sewn on. One can distinguish between 1860 and 1864 Lincoln badges based on whether or not he is depicted with a beard, as Lincoln had not yet grown a beard during the 1860 election. 1864 pins with Lincoln’s face either use bearded photographs or older photographs with a beard drawn in to compensate for the president’s new image.

Celluloid, a type of plastic discovered in 1872 in a system patented by Whitehead and Hoag of Newark, New Jersey, was first popularized for use in political buttons during the 1896 presidential campaign. A paper picture covered by a thin sheet of clear celluloid was arranged over a metal disk. Then, the picture and celluloid were wrapped around the disc and secured with a metal ring that also held a spring-wire pin. William Jennings Bryan lost the 1896 election, but his celluloid pins, such as those in the collection, are popular with collectors and a great example of this exciting new patent.

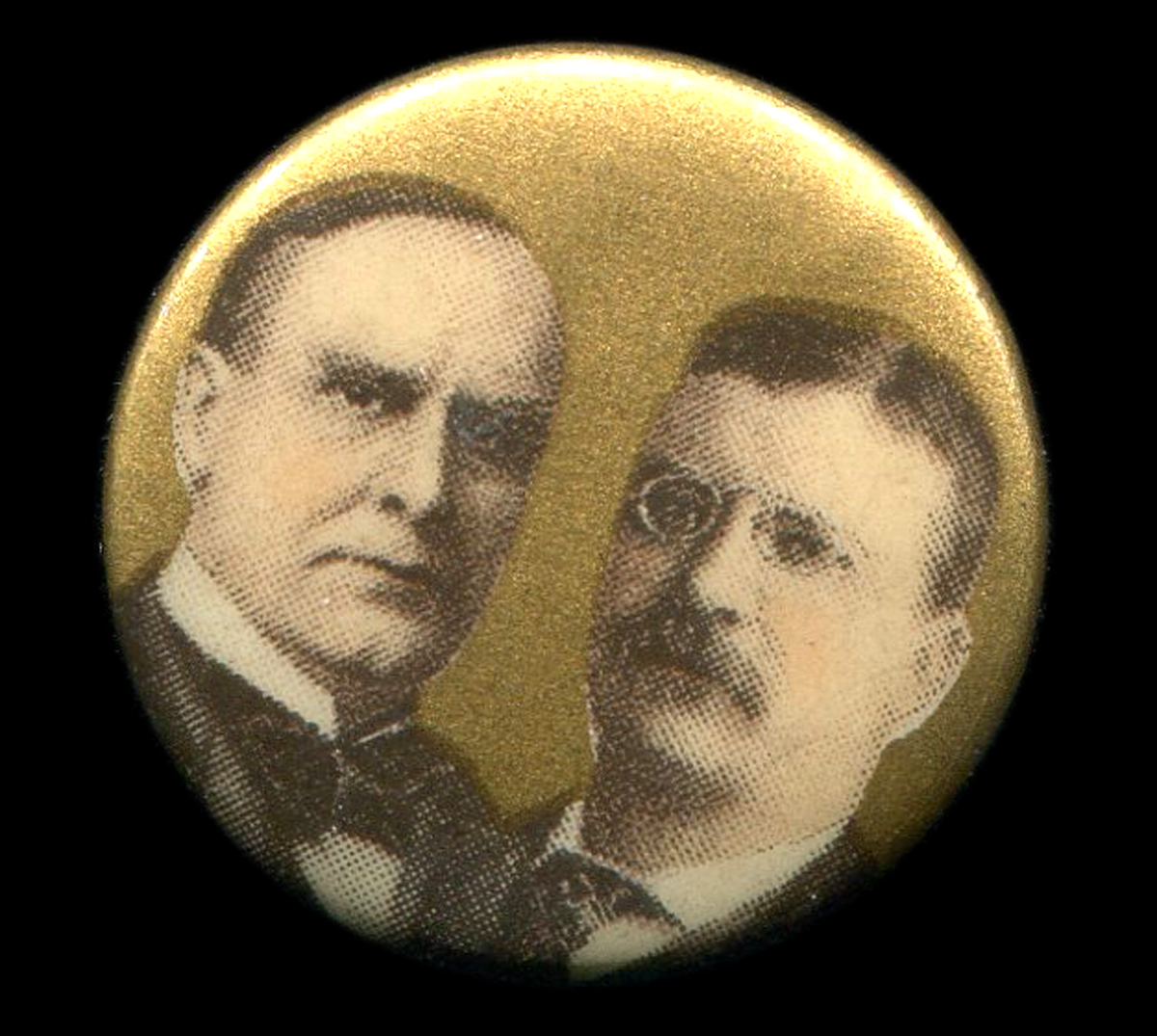

Celluloid pins were wildly popular in campaigns, starting with 1896 and lasting through the 1920’s. The celluloid pins in the MSU collection include those for candidates William McKinley (R, 1896 and 1900), Theodore Roosevelt (R, 1904 and PG, 1912), William H. Taft (R, 1908 and 1912), Woodrow Wilson (D, 1912 and 1916), and Warren G. Harding (R, 1920). During this period, it became popular for organizations to produce their own pins supporting their candidate of choice, such as the First Voter’s Club’s 1904 button for Roosevelt. Businesses would combine a product with a president on a button, as in a 1900 button in the collection that carries endorsements of McKinley and the Ohio Photo Jewelry Company.

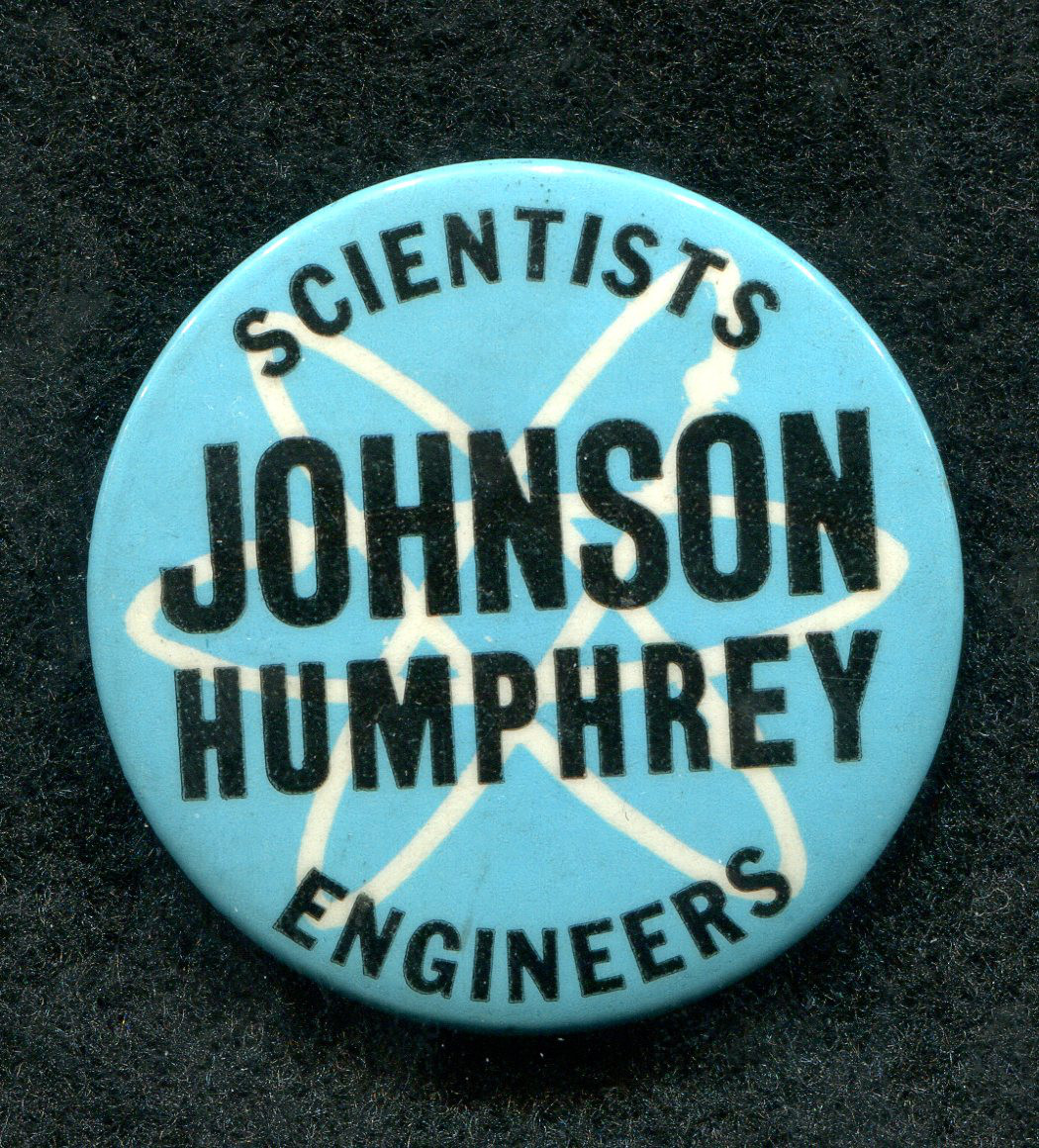

Starting in 1920, designs were printed directly onto a tin sheet for pins using lithography. The pins were punched from the large tin sheet and wrapped around a metal rim, eliminating the need for celluloid, paper and the metal collar. This process was far less expensive, but the images chipped easily and the image quality was not as good. Many lithographed pins in the collections, which span from 1924 for Calvin Coolidge (R) through the 1960s, bear small scratches in their images.

Many of the buttons in the collection represent significant and memorable campaign slogans from American history. Alfred Landon (R, and then governor of Kansas) emphasized his homegrown roots in his 1936 campaign by using bright yellow sunflowers, the state flower of Kansas, as a design element in his campaign materials. Opponent Franklin D. Roosevelt (D) responded with the slogan “Sunflowers Die in November,” and won election in a landslide while Landon only secured two states, neither of which were Kansas. Two styles of Landon’s blue and yellow lithographed pins are included in the MSU Museum collection; the one with yellow felt sunflower petals is a favorite of campaign material collectors.

“I Like Ike!” is one of the most famous slogans in American campaign history. The phrase was coined for Dwight D. Eisenhower (R) in 1951, before he even announced his candidacy for the 1952. It returned when he successfully ran for reelection in 1956, as seen on the large, lenticular print pin in the collection. Lenticular printing was developed in the 1940s, and gives the pin simple animation effects when seen from different angles. This pin moves between “ ‘More than Ever’ I Like Ike” and a picture of Eisenhower’s face.

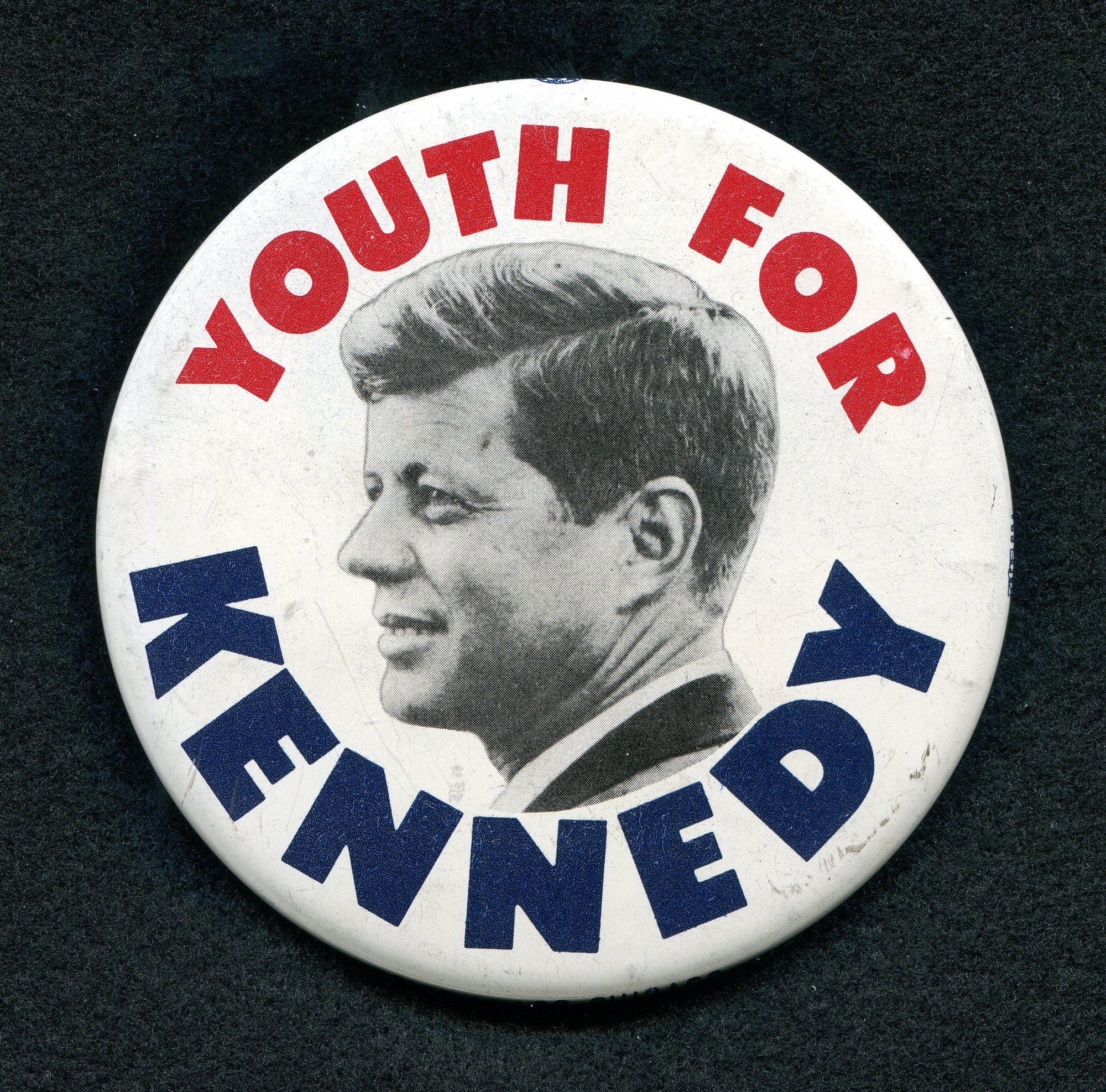

John F. Kennedy’s (D) 1960 campaign included the “Viva Kennedy” public outreach program for Hispanic voters, politicizing Hispanic reform agendas for the first time. Kennedy himself played only a small role in this part of the campaign, but his administration made some of the first Hispanic appointees to leadership positions in the federal government. The “Viva Kennedy” pin in the Museum’s collections comes from this movement.

Sources:

García, Ignacio M. Viva Kennedy: Mexican Americans in Search of Camelot. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2000. Print

Legacy Americana. Legacy Americana LLC, 2010. Web. 1 Nov. 2010.

Sullivan, Edmund B. Collecting Political America. New York: Crown Publishers Inc, 1980. Print.

Donors and Fieldworkers

Chamberlain Memorial Museum, Dr. Oliver Hall, Mrs. Dennis Cossilman, Michigan Republican State Central Committee, Al Woodhams, Tim Fox, Edward Prophet, Jr., Dr. Ira Baccus, Dr. Walters Adams, Dr. Rollin H. Baker, Dr. Marsha MacDowell, Dr. C. Kurt Dewhurst, Val Berryman, Lynne Swanson, Dr. Victor Howard, Jean Spang, Dr. Harriet A. Clarke, Douglas C. Kelly, Ilene Schechter

Landon/Knox presidential button, Kansas, 1936

"Youth for Kennedy" button, 1960

Roosevelt/McKinley campaign button, 1900

"Scientists and Engineers for Johnson Humphrey" button, c. 1960s